The Hindu poet-saint Karaikkal Ammaiyar describes herself as a demon, accompanying the god Siva as he dances in the cremation grounds. She is believed to be the first to write devotional poetry to Siva in the Tamil language and is considered the first of the sixty-three Tamil poet-saints. Written in the sixth or seventh century, her beautiful poetry presents the path of love and service that brings liberation. In Siva’s Demon Devotee, Elaine Craddock provides a historical, literary, and ethnographic exploration of Karaikkal Ammaiyar and her work. An annotated translation of the poet-saint’s 143 verses is included along with an introduction to the Tamil literary tradition. Craddock’s analysis of this poetry in its ancient context and of the narrative tradition that developed around the life of Karaikkal Ammaiyar centuries later reveals cultural tensions concerning women’s roles and the devotional path. Printed Pages: 205

About the Author

Elaine Craddock is Professor of Religion at Southwestern University George Town, Texas (U.S.A). She has contributed several articles to leadings journals around the world.

Introduction

Karaikkal Ammaiyar, the "Mother from Karaikkal," was probably the first poet to write hymns to the god Siva in Tamil, in approximately the mid-sixth century, when the boundaries between Siva's devotees and competing groups were just starting to be articulated in a self- conscious way. Speaking to god in one's mother tongue, rather than Sanskrit, was pivotal to the triumph of Hindu devotionalism over the religions of Jainism and Buddhism that reached the apex of their popularity in South India during the fifth and sixth centuries. The Tamil Saiva tradition considers Karaikkal Ammaiyar the author of four works of poetry. Her powerful poetry is what Indira Peterson calls a "rhetoric of immediacy," as it speaks to a particular community defining itself in a context of competing religious allegiances (1999, 165). Along with the hymns of the later saints, her 143 poems envision a world where devotees can dwell in perpetual bliss with Siva, ridicules those who cannot see that Siva is the only truth, and points to the sophisticated philosophy that would be systematized as Saiva Siddhanta centuries later.

In the southernmost Indian state of Tamilnadu, Saiva Siddhanta developed over many centuries to become the dominant philosophical, theological, and ritual system associated with the god Siva. The tradition was systematized between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries but draws its devotional perspectives from the stories and hymns of the nayaumars, or "leaders," the sixty-three devotees of Siva who were canonized as saints in Cekkilar's twelfth-century hagiography, the Periya Puranam. Seven of these saints wrote poems to Siva between the sixth and ninth centuries. Along with the Alvars who sang to Visnu, these poets were part of the bhakti or devotional movements that began in South India and spread the emotional worship of a personal god throughout the Indian subcontinent.

The devotional movements contained elements of social as well as religious reform, protesting Brahmanical orthodoxy along with the heterodox faiths of Buddhism and Jainism, But this revivalist Hinduism was rooted in the temple, which depended on royal patronage. So, although the devotional ideology undercut caste and gender hierarchies in principle, in practical terms the patriarchal boundaries remained. Statistically, women are not very visible among the Tamil devotional movements: Antal is the only woman Vaisnava saint, and out of the sixty-three Saiva nayanmars, only three are women (Ramaswamy 1997, 120-121). However, the life and poetry of Karaikkal Ammaiyar, the only woman poet among the nayaumars, reveals a fascinating portrait of the localization of a pan-Indian god and the potential space for women in this emerging tradition.

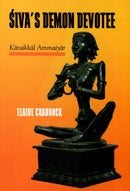

I first became acquainted with Karaikkal Ammaiyar many years ago when I saw Cola bronze images of her in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City and the Metropolitan Museum of New York. I was immediately attracted to her: Her beautiful face wore an expression of pure bliss; her mouth was open, singing her praises for Siva, her Lord. Her enraptured face seemed profoundly at odds with her skeletal, vaguely demonic form. Her striking image led me to read her poetry, and to discover that she indeed had a demon or pey form, in which she lived with Siva in the cremation ground. As I investigated Karaikkal Ammaiyar's life and work, it became clear that there is a continuing tension between the twelfth-century image of her created by Cekkilar and standardized in the ensuing centuries-that of a devoted wife whose love for Siva finally disrupts her domestic life-and the image she presents of herself in her poetry, a pey happily singing in the cremation ground, enraptured by Siva's dance. It turns out that the way I became acquainted with Karaikkal Ammaiyar is a common pattern even in South India, where most people know at least the outline of her story. Worshipers at temples to Siva in Tamilnadu see her image among the sixty-three saints recognized by the Saiva tradition. But not many people are acquainted with her poetry. The divergence between her poetry and her popular life story will be examined in detail in the following chapters.

Description

The Hindu poet-saint Karaikkal Ammaiyar describes herself as a demon, accompanying the god Siva as he dances in the cremation grounds. She is believed to be the first to write devotional poetry to Siva in the Tamil language and is considered the first of the sixty-three Tamil poet-saints. Written in the sixth or seventh century, her beautiful poetry presents the path of love and service that brings liberation. In Siva’s Demon Devotee, Elaine Craddock provides a historical, literary, and ethnographic exploration of Karaikkal Ammaiyar and her work. An annotated translation of the poet-saint’s 143 verses is included along with an introduction to the Tamil literary tradition. Craddock’s analysis of this poetry in its ancient context and of the narrative tradition that developed around the life of Karaikkal Ammaiyar centuries later reveals cultural tensions concerning women’s roles and the devotional path. Printed Pages: 205

About the Author

Elaine Craddock is Professor of Religion at Southwestern University George Town, Texas (U.S.A). She has contributed several articles to leadings journals around the world.

Introduction

Karaikkal Ammaiyar, the "Mother from Karaikkal," was probably the first poet to write hymns to the god Siva in Tamil, in approximately the mid-sixth century, when the boundaries between Siva's devotees and competing groups were just starting to be articulated in a self- conscious way. Speaking to god in one's mother tongue, rather than Sanskrit, was pivotal to the triumph of Hindu devotionalism over the religions of Jainism and Buddhism that reached the apex of their popularity in South India during the fifth and sixth centuries. The Tamil Saiva tradition considers Karaikkal Ammaiyar the author of four works of poetry. Her powerful poetry is what Indira Peterson calls a "rhetoric of immediacy," as it speaks to a particular community defining itself in a context of competing religious allegiances (1999, 165). Along with the hymns of the later saints, her 143 poems envision a world where devotees can dwell in perpetual bliss with Siva, ridicules those who cannot see that Siva is the only truth, and points to the sophisticated philosophy that would be systematized as Saiva Siddhanta centuries later.

In the southernmost Indian state of Tamilnadu, Saiva Siddhanta developed over many centuries to become the dominant philosophical, theological, and ritual system associated with the god Siva. The tradition was systematized between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries but draws its devotional perspectives from the stories and hymns of the nayaumars, or "leaders," the sixty-three devotees of Siva who were canonized as saints in Cekkilar's twelfth-century hagiography, the Periya Puranam. Seven of these saints wrote poems to Siva between the sixth and ninth centuries. Along with the Alvars who sang to Visnu, these poets were part of the bhakti or devotional movements that began in South India and spread the emotional worship of a personal god throughout the Indian subcontinent.

The devotional movements contained elements of social as well as religious reform, protesting Brahmanical orthodoxy along with the heterodox faiths of Buddhism and Jainism, But this revivalist Hinduism was rooted in the temple, which depended on royal patronage. So, although the devotional ideology undercut caste and gender hierarchies in principle, in practical terms the patriarchal boundaries remained. Statistically, women are not very visible among the Tamil devotional movements: Antal is the only woman Vaisnava saint, and out of the sixty-three Saiva nayanmars, only three are women (Ramaswamy 1997, 120-121). However, the life and poetry of Karaikkal Ammaiyar, the only woman poet among the nayaumars, reveals a fascinating portrait of the localization of a pan-Indian god and the potential space for women in this emerging tradition.

I first became acquainted with Karaikkal Ammaiyar many years ago when I saw Cola bronze images of her in the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City and the Metropolitan Museum of New York. I was immediately attracted to her: Her beautiful face wore an expression of pure bliss; her mouth was open, singing her praises for Siva, her Lord. Her enraptured face seemed profoundly at odds with her skeletal, vaguely demonic form. Her striking image led me to read her poetry, and to discover that she indeed had a demon or pey form, in which she lived with Siva in the cremation ground. As I investigated Karaikkal Ammaiyar's life and work, it became clear that there is a continuing tension between the twelfth-century image of her created by Cekkilar and standardized in the ensuing centuries-that of a devoted wife whose love for Siva finally disrupts her domestic life-and the image she presents of herself in her poetry, a pey happily singing in the cremation ground, enraptured by Siva's dance. It turns out that the way I became acquainted with Karaikkal Ammaiyar is a common pattern even in South India, where most people know at least the outline of her story. Worshipers at temples to Siva in Tamilnadu see her image among the sixty-three saints recognized by the Saiva tradition. But not many people are acquainted with her poetry. The divergence between her poetry and her popular life story will be examined in detail in the following chapters.

Payment & Security

Your payment information is processed securely. We do not store credit card details nor have access to your credit card information.